|

|

АкушерствоАнатомияАнестезиологияВакцинопрофилактикаВалеологияВетеринарияГигиенаЗаболеванияИммунологияКардиологияНеврологияНефрологияОнкологияОториноларингологияОфтальмологияПаразитологияПедиатрияПервая помощьПсихиатрияПульмонологияРеанимацияРевматологияСтоматологияТерапияТоксикологияТравматологияУрологияФармакологияФармацевтикаФизиотерапияФтизиатрияХирургияЭндокринологияЭпидемиология |

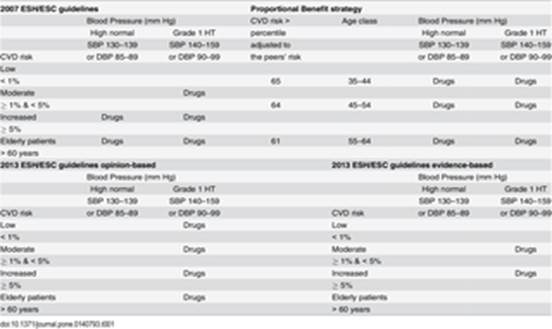

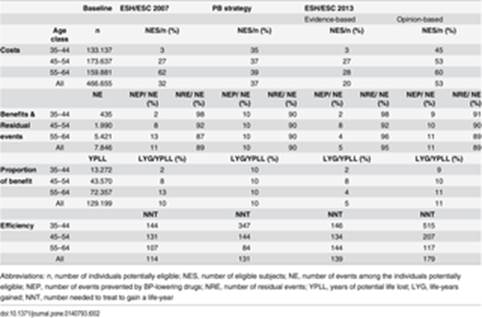

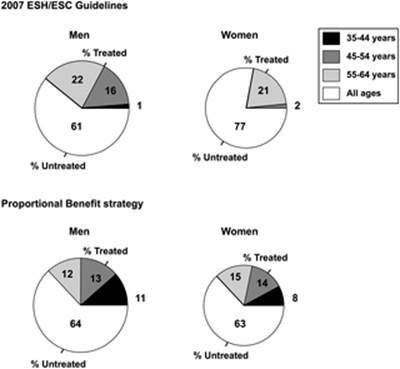

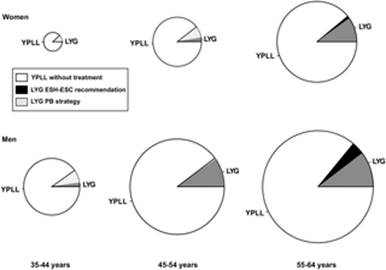

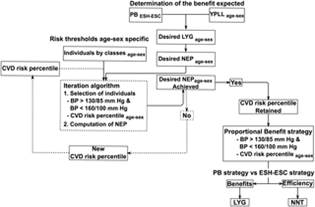

Table 1. Prescription scenarios according to ESH/ESC successive guidelines and the Proportional Benefit strategy.High Risk versus Proportional Benefit: Modelling Equitable Strategies in Cardiovascular Prevention Ivanny Marchant, Jean-Pierre Boissel, Patrice Nony, François Gueyffier Abstract Objective To examine the performances of an alternative strategy to decide initiating BP-lowering drugs called Proportional Benefit (PB). It selects candidates addressing the inequity induced by the high-risk approach since it distributes the gains proportionally to the burden of disease by genders and ages. Study Design and Setting Mild hypertensives from a Realistic Virtual Population by genders and 10-year age classes (range 35–64 years) received simulated treatment over 10 years according to the PB strategy or the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines (ESH/ESC). Primary outcomes were the relative life-year gain (life-years gained-to-years of potential life lost ratio) and the number needed to treat to gain a life-year. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of changes introduced by the ESH/ESC guidelines appeared in 2013 on these outcomes. Results The 2007 ESH/ESC relative life-year gains by ages were 2%; 10%; 14% in men, and 0%; 2%; 11% in women, this gradient being abolished by the PB (relative gain in all categories = 10%), while preserving the same overall gain in life-years. The redistribution of benefits improved the profile of residual events in younger individuals compared to the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines. The PB strategy was more efficient (NNT = 131) than the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines, whatever the level of evidence of the scenario adopted (NNT = 139 and NNT = 179 with the evidence-based scenario and the opinion-based scenario, respectively), although the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines remained the most efficient strategy (NNT = 114). Conclusion The Proportional Benefit strategy provides the first response ever proposed against the inequity of resource use when treating highest risk people. It occupies an intermediate position with regards to the efficiency expected from the application of historical and current ESH/ESC hypertension guidelines. Our approach allows adapting recommendations to the risk and resources of a particular country. Figures

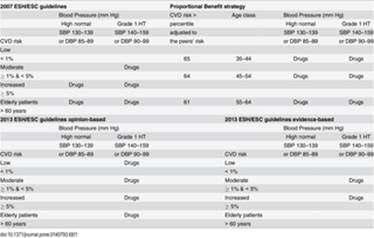

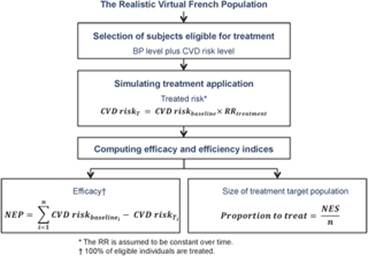

Citation: Marchant I, Boissel J-P, Nony P, Gueyffier F (2015) High Risk versus Proportional Benefit: Modelling Equitable Strategies in Cardiovascular Prevention. PLoS ONE Editor: Angelo Scuteri, INRCA, ITALY Received: November 3, 2014; Accepted: September 30, 2015; Published: November 3, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Marchant et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited Data Availability: All relevant data are available in the paper and its Supporting Information files. Funding: This study was supported by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico-FONDECYT Iniciación a la investigación at CONICYT Chile [11110399] (http://www.conicyt.cl/fondecyt/), and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche France [SYSCOMM 002] (http://www.agence-nationale-recherche.fr/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. NovaDiscovery provided support in the form of a salary for author JPB, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific role of this author is articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section. Competing interests: Jean-Pierre Boissel is employed by NovaDiscovery. There are no patents, products in development or marketed products to declare. This does not alter the authors’ adherence to all the PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials, as detailed online in the guide for authors. Introduction The introduction of the absolute CVD risk as a cornerstone of hypertension management[1] has increased the efficiency of cardiovascular prevention in comparison to the classical recommended BP level alone to identify the target population to BP-lowering drugs[2]. However, the high absolute risk strategy has been criticized by the European Joint Prevention guidelines since the 2003 version[3], mainly because it induces the concentration of health resources on the oldest men due to their highest risk, while young patients at high relative risk, especially women, may often not reach treatment thresholds. Elderly people may be overexposed to treatments, would the absolute risk rule be strictly applied. Yet, as there is no natural risk threshold over which all the benefit from treatment would be observed, the choice has relied on cost-effectiveness principles adopting a unique risk threshold disregarding the age or gender of hypertensive individuals. If treatment effect, expressed as relative risk, is the same whatever the risk level, individuals at the highest risk gain most from risk factor management. However, most deaths in a population occur in low-risk individuals because they are more numerous than high-risk individuals[4]. Moreover, these deaths have heavier consequences in terms of years of life lost. Younger persons at low absolute but high relative risk may well benefit from risk factors control in their future life[5], delaying the occurrence of cardiovascular events. To address the issue of low absolute but high relative risk, the 2007 European Joint Guidelines[6] encourage comparing the individual risk to the risk of peers, i.e. individuals of the same gender and age with ideal levels of risk factors, to decide initiating lifestyle measures to reduce the CVD incidence in low-risk individuals. Revisiting this problem, the latest 2012 version of these Guidelines[1] introduce the risk age approach. The cardiovascular risk age of a person with several cardiovascular risk factors is the age of somebody with the same level of risk but with ideal levels of risk factors. A 40-year old individual may have a risk age of 60 years; illustrating the likely reduction in life expectancy these individuals will be exposed to if preventive measures are not adopted. Nevertheless, no threshold of relative risk has been established nor the question of when drugs treatment would be advisable in this subgroup of individuals has been addressed. The latest guidelines for hypertension management of 2013 stress the importance of the level of evidence when selecting the patients that should be treated with BP-lowering drugs[7]. Unfortunately, the scarcity of evidence does not mean that treatment is indeed inefficacious in some specific population subgroups. It remains difficult to justify leaving untreated those individuals for whom the evidence on treatment benefits is weak. Attempts have been made to provide arguments for a more rational decision process, and lifetime CVD risk prediction models[8] have met increasing interest in providing justification for treating younger individuals at low short-term risk but high lifetime risk. From a less enthusiastic position regarding the irreconcilable dimensions of the potential loss of life due to untreated CVD risk, i.e. greater loss of life expectancy among the younger versus greater number of lives lost due to age-dependent risk increase, many economists hold the view that future health gains should be discounted[9–12], arguing that people give decreasing value to expected benefits in their future life compared to current life[13]. Discounting life expectancies by time preference rates would thus result in higher relative value for the remaining life of older individuals compared to younger individuals if time preference-discounting, case fatality rates and competing risks are considered to estimate the impact of patient age at onset of treatment on the expected benefits of cardiovascular preventive treatments[14]. But how these single, societal or economical criteria could be validated? The fundamental question of which principles should govern the definition of the treatment target population remains unsolved. We propose here a method for the implementation of the peers’ risk approach based on a proportional benefit, derived from solid data largely available with an appropriate reliability: the incidence of cardiovascular deaths within the different categories of gender and age in a population and the proportion of deaths that could be avoided from the overall resources available for prevention. The resulting treatment strategy offers the same Proportional Benefit, or the part of the predicted loss of life that would be prevented by treating the individuals eligible, independently from their age or gender. We assessed the efficacy and efficiency of the Proportional Benefit strategy against the 2007 ESH/ESC recommendation[5] at the scale of a country population, represented by the French Realistic Virtual Population (RVP)[15]. Methods According to the 2007 ESH/ESC recommendation, all the individuals having a BP level greater or equal to 160/100 mm Hg have to be prescribed BP-lowering drugs independently from their CVD risk and conversely, individuals with a BP level < 130/85 mm Hg have no indication of antihypertensive drugs. All these individuals were thus excluded from the analyses and we focused only on the individuals for whom the prescription of BP-lowering drugs was based on the BP level combined with the CVD risk criterion, henceforth called individuals “potentially eligible”: individuals with BP levels in the high normal range and grade 1 hypertension. For the seek of demonstration, we established a reference “conservative” prescription scenario based on the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines where all drug indications that were recommended once lifestyle measures had failed were considered as definite drug indications. Thus, in the reference prescription scenario, individuals with high-normal BP at high risk as well as those with grade 1 hypertension and moderate to high CVD risk were eligible to drugs treatment, disregarding the age. The 2013 guideline version introduced modifications to the 2007 guidelines mainly based on the level of trial evidence [7]. The 2013 guidelines: 1) exclude high-normal BP individuals from drugs prescription, 2) consider grade 1 hypertension and low risk individuals as eligible to treatment (although it cannot be strongly recommended since evidence is weak) and 3) recommend that, in elderly patients, drug treatment should be initiated only when SBP is ≥ 160 mm Hg, although it may be considered when SBP is in the 140–159 mm Hg range. We established two new prescription scenarios assuming different interpretations of the 2013 guidelines: 1) an evidence-based scenario: excluding grade 1 low risk and grade 1 elderly patients from treatment, and 2) an opinion-based one: including grade 1 low risk and grade 1 elderly patients (Table 1).

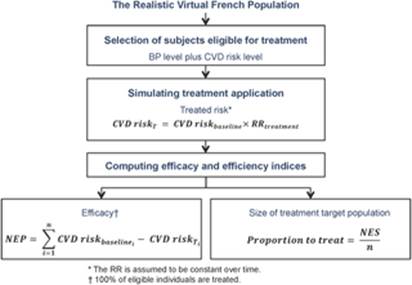

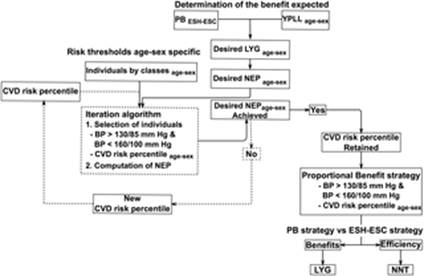

Table 1. Prescription scenarios according to ESH/ESC successive guidelines and the Proportional Benefit strategy. We designed the Proportional Benefit strategy as an alternative approach to select the individuals eligible to BP-lowering drugs treatment while attaining at least the same overall benefit in terms of life-years gained as with the 2007 European guideline application. This benefit was distributed proportionally, i.e. with the same ratio of number of fatal CVD events to prevent over the expected number of fatal CVD incident events across the different categories of individuals. The desired number of events prevented was used as a constraint to adjust the risk thresholds within each category of individuals in order to indicate BP-lowering drugs to the mild hypertensives with the highest risk compared to their peers. We examined the benefits and efficiency of our PB strategy against the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines when implemented on the French primary prevention RVP, a one million individual-data base that reproduces the demographic composition of the nation in the age range 35–64 years and preserves the original co-variations of the individual characteristics, mainly modifiable and non modifiable cardiovascular risk factors[15]. We used the SCORE equations for low risk regions[16] to compute the 10-year fatal CVD risk for each individual (S1 Data, S2 Data). Virtual individuals were separated by sex and stratified by 10-year age categories. Primary outcomes were life-years gained in the years of potential life lost (relative life-year gain), and the number of subjects needed to treat to gain a life-year (NNT) by categories of gender and age. Simulations and all statistical analyses were performed in the R 2.14.1 statistical computing environment[17]. Дата добавления: 2015-11-26 | Просмотры: 540 | Нарушение авторских прав |

10(11): e0140793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140793

10(11): e0140793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140793